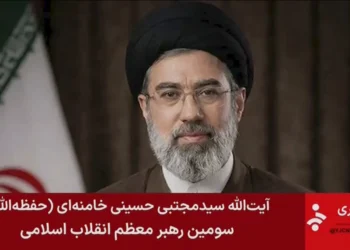

NAIROBI (Realist English). Kenya is witnessing its most intense wave of protests since President William Ruto took office, as disillusionment with his leadership hardens into open defiance. Demonstrators across the country — especially youth — are now calling for his early exit, brandishing slogans like “WANTAM” (“one term”) and chanting for his removal by 2027, if not sooner.

The latest protests, sparked by the death of a blogger in police custody, have become a flashpoint for widespread frustration with Ruto’s administration. Many see his presidency as a betrayal of campaign promises to uplift the working class. Instead, his government has introduced sweeping tax hikes, removed fuel subsidies, and courted billion-dollar deals with foreign investors — moves that critics say burden the poor and benefit the elite.

“He has control of the institutions, but he doesn’t have control of the people,” said Karuti Kanyinga, professor at the University of Nairobi, who described Ruto as possibly “the most hated man in Kenya.”

Last year’s anti-tax protests ended violently, with at least 22 people killed and a failed attempt to storm parliament. Ruto vowed such unrest would “never happen again,” but tensions have only escalated. The recent flare-up comes amid growing public anger over corruption, government opacity, and alleged repression.

Some Kenyans now refer to the president as “Zakayo” — a nod to the biblical tax collector Zacchaeus — or simply “mwizi” (thief). Demonstrators cite broken promises, such as a scrapped $2bn deal with India’s Adani Group to manage Nairobi’s main airport, as evidence that Ruto is out of touch and unwilling to listen.

His aggressive push to expand the tax base — often justified as necessary to avoid national bankruptcy — has also drawn criticism for deepening inequality. Speaking at Harvard last year, Ruto said he refused to “preside over a bankrupt country.” But on the streets of Nairobi, many believe they’re paying the price.

“There’s a sense that things haven’t changed since last year’s protests,” said Meron Elias, Kenya analyst at the International Crisis Group. “People feel ignored, and the grief is still raw.”

Adding to the volatility is Ruto’s track record of political maneuvering. He famously outflanked former president Uhuru Kenyatta, then turned on his own deputy, Rigathi Gachagua, whose impeachment in October was widely seen as orchestrated from above. Analysts say such moves reinforce perceptions of Ruto as intolerant and power-hungry.

His 2022 victory, powered by the populist “hustler nation” campaign, had initially resonated with informal workers and low-income voters. But that goodwill has since evaporated.

“It’s a case of overpromising and underdelivering,” said Eric Nakhurenya, a Nairobi-based policy expert. “That’s why Kenyans are angry.”

Ruto continues to defend his agenda and has warned that ongoing protests risk tearing the country apart. “If there’s no Kenya for William Ruto, there’s no Kenya for you,” he told demonstrators last week.

But that defiant tone may only deepen the rift between the president and the public — a divide that now defines Kenya’s political landscape just three years into his presidency.