CARACAS (Realist English). A day after U.S. special forces swept into the Venezuelan capital and detained former president Nicolas Maduro, the country’s new interim leader, Delcy Rodríguez, convened her cabinet at Miraflores Palace beneath portraits of Hugo Chávez and the now-jailed Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores.

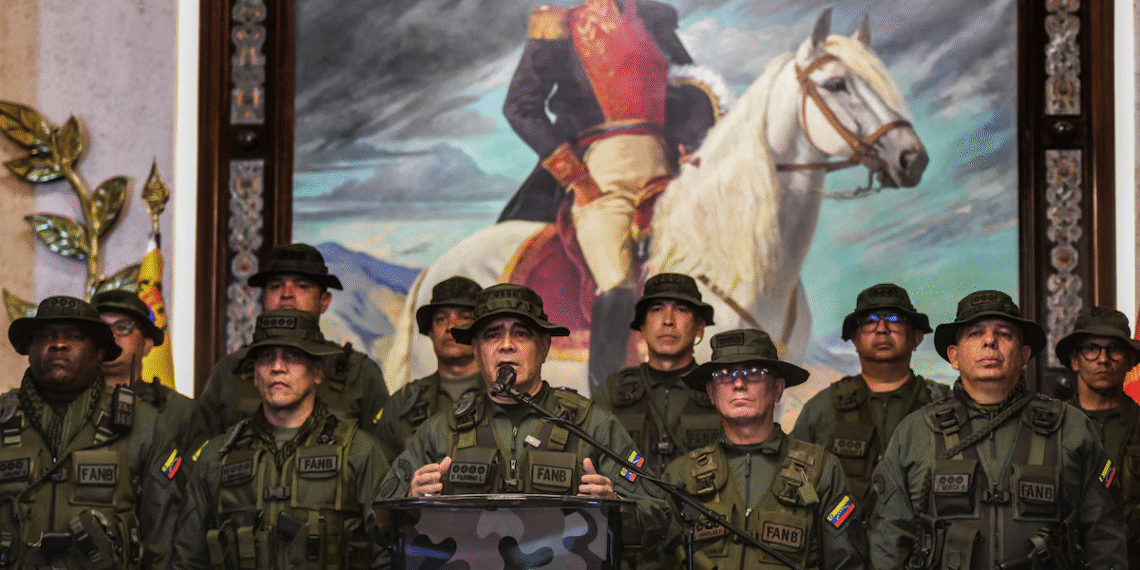

Seated beside Rodríguez were the figures many analysts say now hold the decisive levers of power in Venezuela: Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino López, dressed in military fatigues, and Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello, a hard-line Chavista whose influence extends deep into the security services and the ruling party’s informal power networks.

While international attention has focused on whether Rodríguez will comply with White House demands to open Venezuela’s vast oil and mineral resources to U.S. companies, scholars and current and former officials say the interim president controls only part of the state apparatus. The country’s coercive and economic power, they argue, remains firmly in the hands of Padrino and Cabello — long-standing loyalists of the Chávez–Maduro system who oversee the armed forces, police, intelligence services and key commercial sectors.

“There are three centers of power,” said a former senior U.S. State Department official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “And Delcy is going to find out very quickly that she cannot deliver everything Washington wants.”

Both Padrino and Cabello are wanted by U.S. authorities on drug-trafficking charges and face multimillion-dollar bounties. According to U.S. prosecutors, they used their official positions to facilitate narcotics flows and profit from illicit revenue streams — allegations they have denied in the past.

Analysts describe Venezuela’s political system as a fragmented, factional structure that hardened under Maduro’s rule. After succeeding Chávez in 2013, Maduro increasingly relied on repression and patronage rather than popular legitimacy, transferring control of mining, ports and food distribution to the military. This consolidation dramatically expanded Padrino’s power and embedded the armed forces deeply into the economy.

“The military became its own branch of power,” said Carolina Jiménez Sandoval, head of the Washington Office on Latin America. “Its influence is both formal and informal, and it is far more extensive than many outside observers realize.”

Cabello, meanwhile, is widely viewed as the regime’s most unpredictable figure. A veteran of Chávez’s 1992 coup attempt, he has built a reputation as an enforcer with direct influence over police units, intelligence agencies and pro-government militias known as colectivos. These groups have recently expanded their presence in Caracas, setting up checkpoints and detaining civilians amid fears of unrest and foreign interference.

“Cabello is a brutal but calculating actor,” said Geoff Ramsey of the Atlantic Council. “He understands that his leverage comes from the implicit threat of chaos if his interests are ignored.”

The overlapping family, military and economic networks surrounding Cabello further complicate any external negotiation. His brother heads Venezuela’s customs and tax authority, his wife sits in the National Assembly, and close relatives hold senior intelligence posts — a concentration of power that researchers say has only grown since Maduro’s fall.

For Washington, this reality underscores the difficulty of shaping Venezuela’s future through pressure alone. President Donald Trump has said the United States is now “in charge” of Venezuela, while Secretary of State Marco Rubio has suggested a more indirect strategy built around sanctions and oil controls. But experts warn that U.S. policymakers may be underestimating the resilience — and ruthlessness — of Venezuela’s internal power brokers.

“It’s not just an authoritarian regime,” said Venezuelan investigative journalist Roberto Deniz. “It’s a kleptocratic system with multiple fiefdoms. The overriding objective is not governance or reform, but the preservation of power at any cost.”

Whether Delcy Rodríguez can navigate these rival centers, placate U.S. demands and prevent further instability remains uncertain. As one former U.S. diplomat put it, “It is the same regime, under different management — and it is a very rough start.”