NEW DELHI (Realist English). Five years after mass farmer protests forced Prime Minister Narendra Modi to repeal controversial agricultural reforms, rural unions are again mobilizing — this time over trade talks with U.S. President Donald Trump.

Daljinder Singh Haryaoo, a maize and rice grower from Punjab, said he is ready to “climb back on his tractor” if New Delhi concedes too much to Washington.

“Allowing U.S. crops and food products into India through a trade deal will finish us,” said Singh Haryaoo, a member of a powerful farming union representing tens of thousands across Punjab’s farmlands.

The warning comes amid intense negotiations between India and the U.S., with Washington pressing for greater market access for its agricultural exports. Indian officials have long excluded agriculture from trade pacts, arguing that opening the sector could devastate millions of small farmers — a crucial voting bloc ahead of four regional elections in the next seven months.

Modi has pledged to stand “like a wall” against any policy that harms farmers’ interests. Agriculture Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan recently called farming “the backbone of India’s economy, and farmers its soul.”

Nearly half of India’s workforce depends on agriculture, which contributes about 20% of GDP. The sector, dominated by small and fragmented holdings — averaging just over one hectare per farm — remains largely unprofitable.

In 2020, massive farmer protests against deregulation left Modi politically bruised and forced him to abandon plans to liberalize grain markets. This time, the risk stems from U.S. pressure on trade barriers. Washington has criticized India for blocking imports of maize, rice, and dairy products, where tariffs range from 15% to 80%.

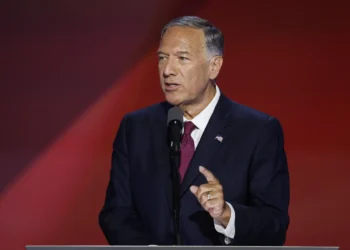

U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick accused New Delhi of refusing to import “a single bushel” of U.S. maize. Trump has warned that unless India reduces imports of Russian oil, Washington will maintain “massive tariffs” on Indian goods.

While full liberalization is unlikely, sources in New Delhi say India may allow limited imports — such as maize for ethanol production — or set strict quotas. However, most U.S. maize and soybeans are genetically modified, creating additional regulatory hurdles under India’s ban on GM crops.

Rural leaders have issued stark warnings.

“For farmers, a free trade agreement is unimaginable,” said Avik Saha of the Samyukt Kisan Morcha, a coalition of farmers’ unions. “Imports will push prices further down — it’s written on the wall.”

Even groups aligned with Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are voicing concern. Mohini Mohan Mishra, general secretary of the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, said any government that compromises farmers’ interests “will be dragged down by voters.”

The dairy sector, employing 80 million people, has also pushed back. “India doesn’t need dairy from outside — we’re already the world’s largest milk producer,” said Rupinder Singh Sodhi, head of the Indian Dairy Association.

Ajay Bhalothia of the All India Rice Exporters’ Association added that U.S. demands for duty-free access to Indian markets are “not viable.”

Back in Punjab, trucks carry slogans reading “No farmer, no food.” For Singh Haryaoo and his peers, the message is clear:

“Our entire livelihood is at stake,” he said. “If Modi opens the market to subsidized U.S. rice, maize, and dairy, we will hold an even bigger protest than before.”