CHICAGO (Realist English). Hundreds of Texas National Guard soldiers gathered Tuesday at an Army Reserve base outside Chicago, as President Donald Trump signaled he may invoke the Insurrection Act — a centuries-old law allowing the use of military force within the United States — to deploy troops in Democratic-led cities without state consent.

The move has intensified a constitutional showdown over the limits of presidential power, drawing sharp criticism from governors, legal experts, and former military officials.

Trump told reporters in the Oval Office that he was keeping “all options open,” saying the federal government must act if local leaders “can’t do the job.” “If you look at Chicago, it’s a great city with a lot of crime — and if the governor can’t handle it, we will,” he said.

The Insurrection Act, last used in 1992 during the Los Angeles riots, grants the president authority to deploy the military in response to rebellion or unrest. Normally, National Guard forces operate under state control, and federal law bars troops from domestic policing. Invoking the act would override those restrictions and allow soldiers to make arrests — a move legal scholars call an extraordinary escalation.

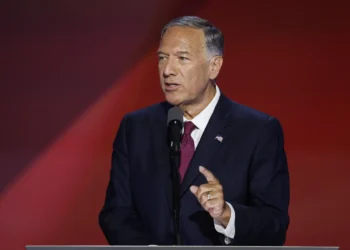

“This is an extremely dangerous slope,” said Maj. Gen. (Ret.) Randy Manner, former acting vice chief of the National Guard Bureau. “It essentially says the president can do whatever he chooses. It’s the definition of dictatorship.”

Court challenges and deployments

Federal judges have already begun to intervene. A judge in Oregon temporarily blocked troop deployments to Portland, while another in Illinois has allowed the Chicago operation to proceed pending further review.

Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker accused Trump of using service members as “political props,” calling the deployments “illegal and unconstitutional.” His administration, along with the City of Chicago, filed suit to block the federalization of 300 Illinois Guard troops and the arrival of 400 Texas Guard soldiers.

At a hearing Monday, Justice Department lawyers confirmed that the Texas contingent was already en route to Illinois. Judge April Perry allowed the deployment for now but ordered the government to respond to the lawsuit by Wednesday.

Trump’s latest deployments follow earlier operations in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., launched under his campaign to combat crime and illegal immigration. In Chicago and Portland, however, local officials report that protests have been small and largely peaceful — a stark contrast to the “war zone” rhetoric used by the White House.

Political and public reaction

Civil rights advocates and Democratic lawmakers have warned that Trump’s threats to use the military against American civilians mark a grave departure from democratic norms.

Last week, the president told senior military officers that U.S. cities could serve as “training grounds” for troops — a remark that drew outrage from opponents and unease within the Pentagon.

Trump’s critics say the renewed focus on “law and order” is part of his broader effort to consolidate executive power and silence dissent. Since beginning his second term in January, Trump has repeatedly clashed with courts and governors over the scope of presidential authority.

For now, the troops stationed in Elwood, about 50 miles southwest of Chicago, have not entered the city itself. The Defense Department said their mission is limited to protecting federal facilities and assisting federal agents, though it confirmed that troops have the authority to detain individuals temporarily.

Whether Trump formally invokes the Insurrection Act could depend on how courts rule in the coming days. Legal experts note that the Supreme Court has historically deferred to the president’s judgment in determining whether the act’s conditions — such as rebellion or obstruction of federal law — are met.

If Trump proceeds, it would mark the most aggressive domestic use of the U.S. military in more than three decades — and a defining test of the boundaries of presidential power in modern American history.