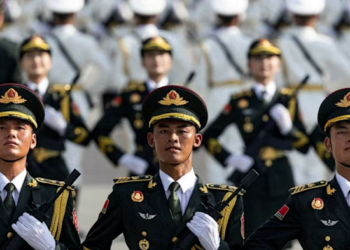

Putin and Xi reaffirm strategic partnership in New Year video talks

MOSCOW (Realist English). Russian President Vladimir Putin held a video conference with Chinese President Xi Jinping on February 4, marking...

Read moreCommittee for the Defense of the AAC in Bratislava Calls for Release of Detained Clergy

BRATISLAVA (Realist English). A meeting of the Committee for the Defense of the Armenian Apostolic Church (AAC) and Christianity in...

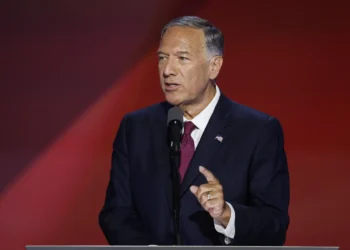

Read moreSouth Africa’s Democratic Alliance leader to step down amid party turmoil

DURBAN (Realist English). John Steenhuisen, leader of South Africa’s Democratic Alliance (DA), said he will step down in April after...

Read moreDivisions in European Parliament stall progress on digital euro

BRUSSELS (Realist English). The European Union’s plan to introduce a digital form of cash cannot move forward unless the European...

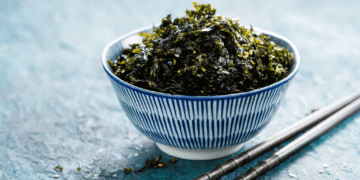

Read moreRising global demand drives record prices for South Korea’s dried seaweed

SEOUL (Realist English). Dried seaweed, known locally as gim, has long been a cheap staple on South Korean dining tables....

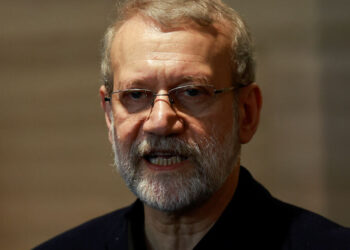

Read moreIran warns EU states of retaliation after IRGC blacklisting

TEHRAN (Realist English). Iran’s top security official Ali Larijani has warned that the armed forces of European Union member states...

Read more