BEIJING (Realist English). China’s energy security and Middle East ambitions are under growing pressure as Israel’s attacks on Iran threaten to sever Beijing’s access to key oil suppliers and undermine its position as a rising diplomatic power in the region.

For years, China has relied on cheap Iranian oil and stable Gulf supplies to meet the needs of the world’s largest crude importer. But as the regional conflict deepens, that model is under threat. President Xi Jinping this week urged all sides to avoid further escalation and called for a political solution, while reaffirming opposition to U.S. sanctions that restrict China’s “normal trade” with Iran.

“This is a serious concern for China,” said Gedaliah Afterman, a China–Middle East specialist at Israel’s Abba Eban Institute. “If tensions continue, Beijing risks losing both a strategic partner and a key energy supplier.”

Since the reimposition of U.S.-led sanctions in 2018, Tehran has become economically dependent on Beijing, which buys the bulk of its oil exports and supplies vital goods including machinery and nuclear components. Iranian crude accounted for up to 15% of China’s oil imports last year, but volumes have since dropped due to growing fears of secondary U.S. sanctions.

According to Kpler and Bernstein, Iranian exports fell from 2.4mn barrels per day in September 2024 (with China buying 1.6mn) to 2.1mn by April 2025, with China’s share declining to just 740,000 barrels per day. Malaysia is also used as a transshipment point to mask Iranian origin.

The conflict’s most disruptive potential lies in the Strait of Hormuz, a vital chokepoint for Gulf oil and LNG. Iran has threatened to block the strait, through which hundreds of billions of dollars in energy flows to China each year. Saudi Arabia, China’s top oil supplier after Russia, and Qatar and the UAE, which provide more than 25% of China’s LNG, could be affected if fighting escalates.

China does not disclose the size of its strategic oil reserves, but Oxford Institute analyst Michal Meidan estimates it holds 90–100 days’ worth of supply. Yet any sustained disruption would likely force Chinese buyers to turn to the spot market, driving up costs.

At home, the crisis reinforces Xi’s long-term policy shift toward energy self-sufficiency. Renewables now account for over 56% of China’s installed electricity capacity, up from one-third a decade ago. “If it wasn’t happening fast enough before, it will be happening even faster now,” said Neil Beveridge of Bernstein.

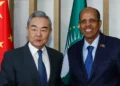

Still, China’s ability to shape events in the Middle East appears limited. Despite brokering a 2023 Saudi–Iran rapprochement and promoting its 12-point peace plan for Ukraine, Beijing has remained largely passive during the Israel–Iran war — just as it did during last year’s collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria.

Analysts warn this could damage China’s image as a credible alternative to U.S. leadership. Yun Sun of the Stimson Center noted that a weakened Iran would widen Washington’s influence in the region and erode Beijing’s leverage. “The collapse of Iranian power is not good news for China,” she said.

Despite this, Beijing continues to engage. Xi recently signed a 25-year cooperation pact with Tehran, and Iran joined the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2023. Coordination with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states will now be critical as China navigates a new phase of uncertainty in the region it once hoped to anchor.